Start typing and press enter to search

.jpg)

Jamie is Redvespa's Head of Experience and former-museum curator; as an 8-year-old, when his walk home from school took him past a museum, the realisation that he could go inside and explore sparked a lifelong passion for curiosity and storytelling.

In 2024, I set myself the goal of reading 50 books. I went hard and early, finishing #50 well inside the first half of the year.

By December 31st, I’d read precisely 50 books.

In 2025, I set no such goal … and spent the entire year reading a single book.

Heading into 2026, with a little more summer reading time up my sleeve and with a desire to reduce idle scrolling, I set the same 50-book goal.

Three weeks into the year, and I’m about to complete book #6.

Hard and early, again.

What’s different this time is a shift in genre, with thrillers taking up most of my reading time. I’m finding them a bit hit or miss. Not uncommon for books, especially because I absolutely judge/pick books on their covers, but it’s something that’s given me pause as I’ve marched from the female protagonist alone in an isolated house to the wrongly imprisoned employee of a rich family to the son seeking revenge for a wronged father.

Then, Redvespa’s Head of Consulting, Matt Duce shared a phrase with me,

“The brain is a guessing machine.”

When I’m reading these thrillers, my brain is bringing an archive of pop-culture references to movies, TV shows, and other stories where the protagonist runs the wrong way, where the most obvious suspect is far from the perpetrator, where the first twist is seldom the last.

The thrillers I’m reading where the guessing machine is accurate are getting three stars on Goodreads: an entertaining read, with an element of predictability.

The ones which deliver a five star story involve “breaking” the guessing machine, forcing me to be more curious, imaginative, and engaged in the story.

Our guessing machines don’t stop at circumventing exposition in novels, though.

In the office, the stakes are higher than a Goodreads rating. When stakeholders step into a project, their brains are already running predictive software. They look at a project brief the way I look at a book cover. Based on past migrations, system swaps, or restructures, they think they already know how the story ends.

The danger of a project led by unchecked guessing machines is budget blow-outs, staff burn-outs, and lights-out on roles, departments, and businesses. When a stakeholder thinks they’ve seen this story before, without challenge or engagement, they stop being curious. They stop asking “Why” and start assuming “What.”

To move from a predictable three-star project to a five-star transformation, we have to intentionally break the guessing machine.

The idea of the brain as a guessing machine comes from psychology and neuroscience, but it’s become central to modern storytelling. Our brains constantly predict what comes next, based on what we already know. Bringing this understanding to how we communicate enables us to move from simply sharing information to engaging audiences and bringing them with us.

The gap between what we know and what we want to know is called the Information Gap. In the 1990s, George Loewenstein described curiosity as a response to this gap — a feeling of deprivation that compels us to seek answers.

In projects, we often close this gap too quickly. We lead with solutions before stakeholders have felt the weight of the problem. The guessing machine never gets irritated, so curiosity never turns on.

TED Talks show this principle in action. Many speakers begin by creating a gap through paradox or “wrongness.” Sir Ken Robinson’s “Do schools kill creativity?” works because it challenges our existing mental models.

For most of us, this approach presents us with information which doesn’t fit the models we’ve built, so we sit up, pay attention, and feed our knowledge deprivation with curiosity.

This approach is ancient. The Odyssey, the world’s most enduring narrative and the foundation of the Hero’s Journey format, begins in medias res, in the middle. This creates immediate tension and ensure the gaps will be filled with intent and by the storyteller.

In business, a practical version of this is the SCQA model - Situation, Complication, Question, Answer - a hero’s journey for the 9 to 5.

The Complication is the plot twist, the moment that breaks the guessing machine and surfaces a Question the brain is compelled to resolve. Often, you don’t even need the Answer yet. Present the SC. Let stakeholders engage with the QA.

Or, break the model to break the machine; lead from the middle with the Complication or the Question.

Beginning your story in the middle is an approach which helps engage people, making their guessing machines curious in search of the bridge between what they know and what they need to know.

Information sticks when the brain feels that need.

Engagement is one thing. Stickiness is another.

Think about the last time you flew.

You sat down, momentarily felt annoyance at the seats beside you filling with strangers, fired off those last few emails, ignored the first reminder to turn off your wifi, reluctantly acquiesced to the second reminder, and then sat staring past the screen displaying the safety briefing, thinking about the replies those last few emails would receive. Five minutes later as you hit the customary take-off turbulence, you wonder, where did they say the lifejackets were?

Now think about that time when the screens were offline.

You sat down, momentarily felt annoyance at the seats beside you filling with strangers, fired off those last few emails, ignored the first reminder to turn off your wifi, reluctantly acquiesced to the second reminder, and then sat staring past … wait, there wasn’t a screen. Instead, there was an enthusiastic flight attendant on the microphone,

"Under your seat you'll find a copy of the airline magazine from 2019 and the half-eaten airport bagel you dropped during boarding.

Conveniently, your life jacket is also located there in a small pouch."

You didn’t forget where your lifejacket was.

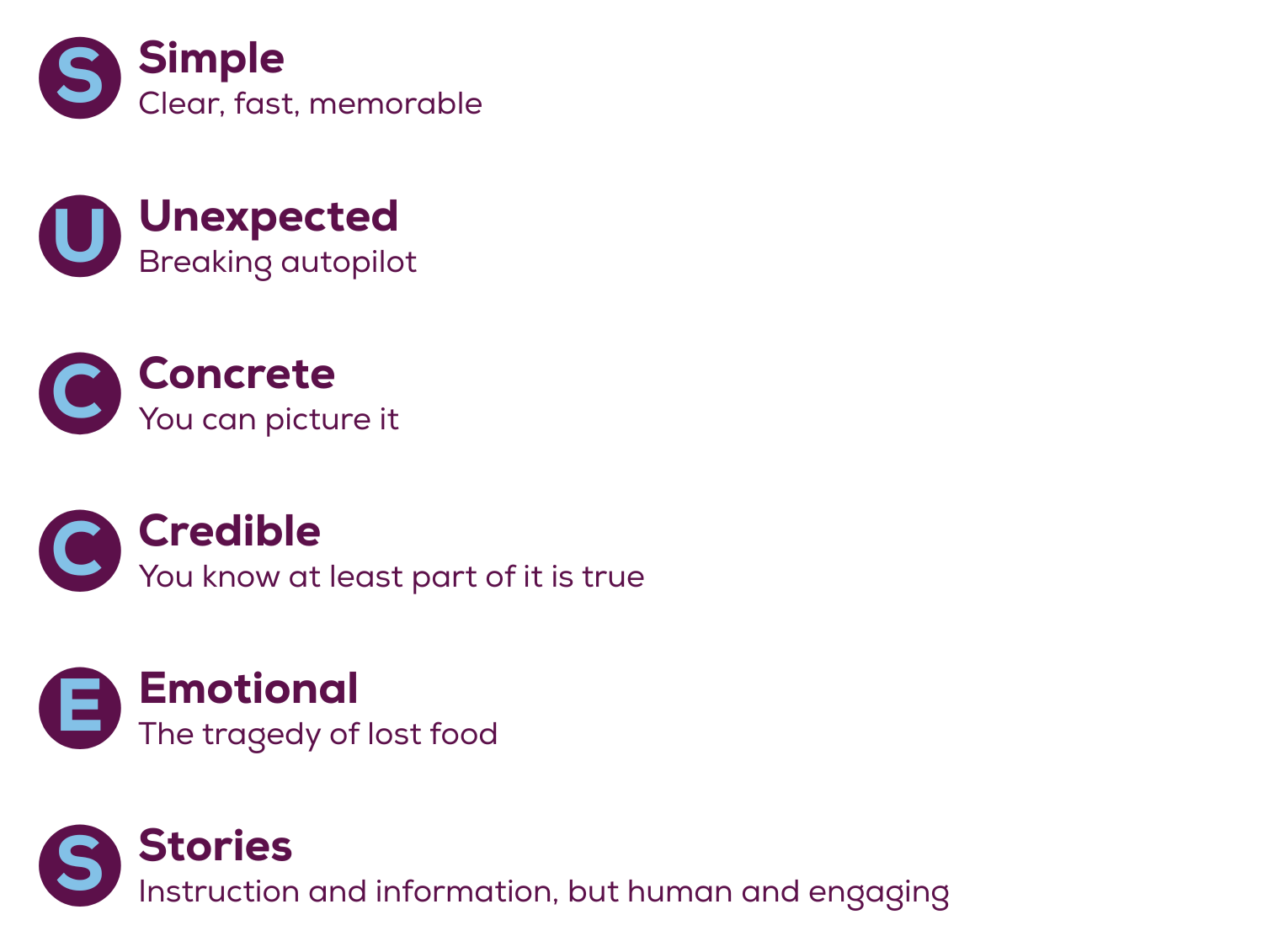

That flight attendant wasn’t just being funny, they leaned into the unexpected, one of the core pillars of the SUCCES model for sticky ideas, created by Chip and Dan Heath (brothers who literally wrote the book on stickiness):

By subverting your safety-briefing archive, they triggered a prediction error. Your brain stopped filtering and started recording.

No announcement from the pilot required. The flight attendant stuck the landing.

Ultimately, if act one of your story looks exactly like the last five act ones people have sat through, you aren't telling a story; you're creating background noise.

Harness the information gap, bring the unexpected, break the guessing machine.

Header image: Patrick Tomasso on Unsplash

Link copied to clipboard