Start typing and press enter to search

.png)

Jamie Bell is Redvespa's Head of Experience and a key cog in our thinking around curiosity. Together with our BAs and our Head of Consulting, Matt Duce, he has delivered curiosity workshops designed to move curiosity from a nice-to-have skill to a full-on superpower. Curious? Get in touch."

As winter became spring in 1837, Charles Darwin would sit at his desk, surrounded by small notebooks filled with sketches, specimens, and half-formed thoughts.

He wasn’t writing his most famous work, On the Origin of Species, yet, that would come much later. At this point, he was simply collecting: recording what he saw, what he wondered, what he couldn’t yet explain.

His entries jumped from geology to biology to the behaviour of finches; from careful measurements to scattered impressions written in haste. Each note led to another question, each question to another observation.

Darwin wasn’t chasing certainty. He was following curiosity: broad and specific, perceptual and epistemic, facts and experiences, all at once.

He was, in every sense, a “Compass”.

We often think of curiosity as a single trait, something you either have or don’t. But curiosity has shapes and shades, ways of showing up that are as individual as fingerprints.

At Redvespa, we’ve been exploring these shapes and building a model of curiosity and how it plays out. The intent isn’t purely to categorise curiosity, but to understand how it moves: between people, projects, passions. We think, the more we recognise our own patterns of curiosity, the better we can harness them for our learning, our work, and our relationships.

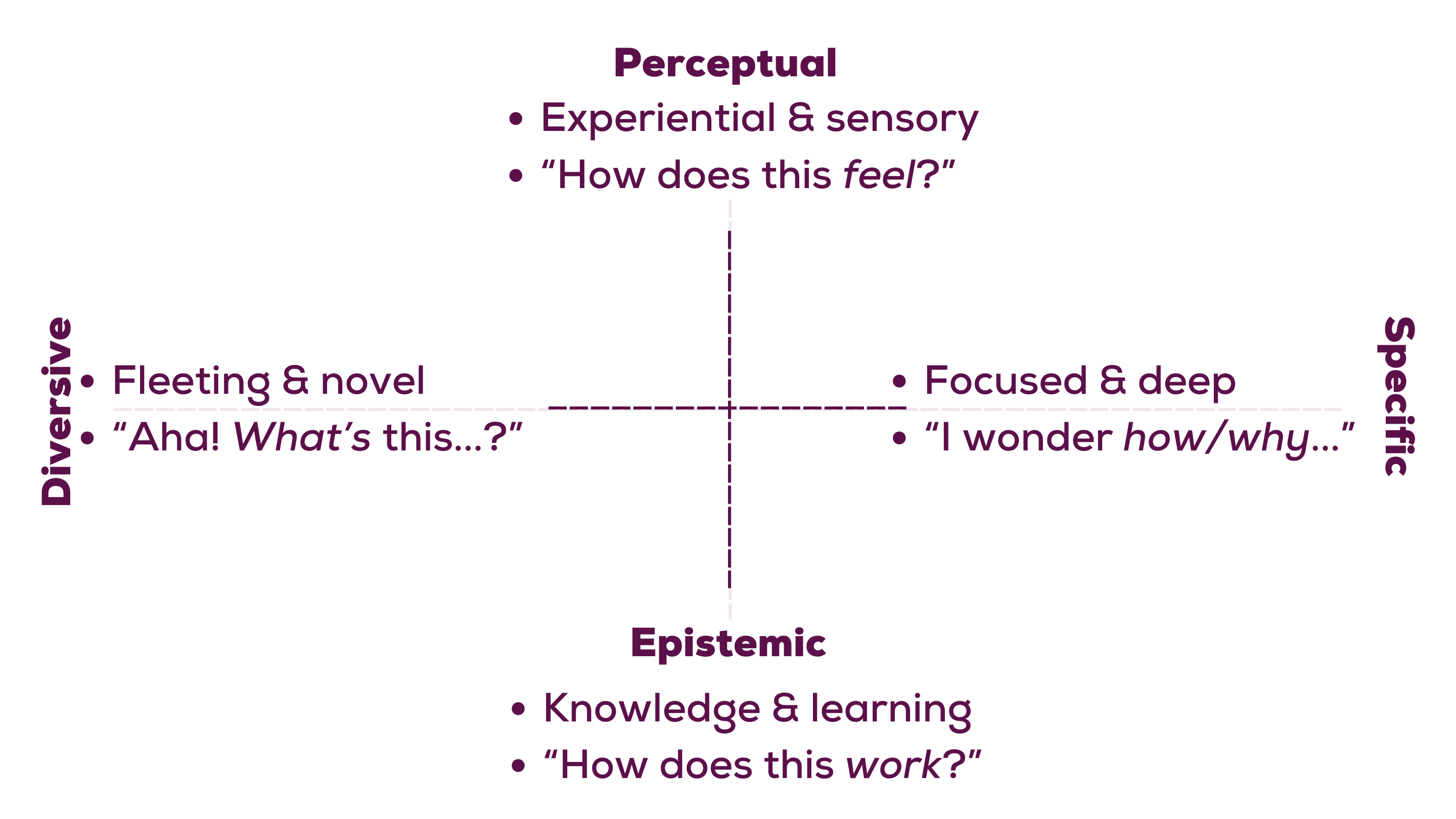

Curiosity has been studying, philosophised, and contemplated for a long time. That means, there are a huge range of theories around the topic. At Redvespa, we’ve been considering curiosity as moving across two key dimensions: Broad ↔ Specific and Perceptual ↕ Epistemic.

Some curiosity casts a wide net. Psychologists call it diversive; curiosity that explores for exploration’s sake. It’s what draws us to new ideas, people, and perspectives; curiosity that feeds imagination: “What else is out there?”

Other curiosity prefers depth. Known as specific curiosity, it’s the kind that stays with a question until it finds an answer. It values focus and precision, turning discovery into understanding.

Broad curiosity gives us range; specific curiosity gives us rigour. And the best work often happens when the two are used together, when we explore widely, then narrow down with intent.

The second dimension captures how we experience curiosity.

Perceptual curiosity is sensory and emotional. It begins with being present, experiencing, feeling, and noticing. It’s the flicker of something interesting, a pattern that doesn’t fit, a feeling that something matters even before we know why.

Epistemic curiosity, by contrast, seeks understanding. It’s logical and structured, determined to make sense of what we’ve observed. It asks, why does this work the way it does?

Psychologists have been studying this balance since Daniel Berlyne’s work in the 1950s, and more recent neuroscience suggests the two are intertwined: perceptual curiosity lights the spark, epistemic curiosity keeps it burning.

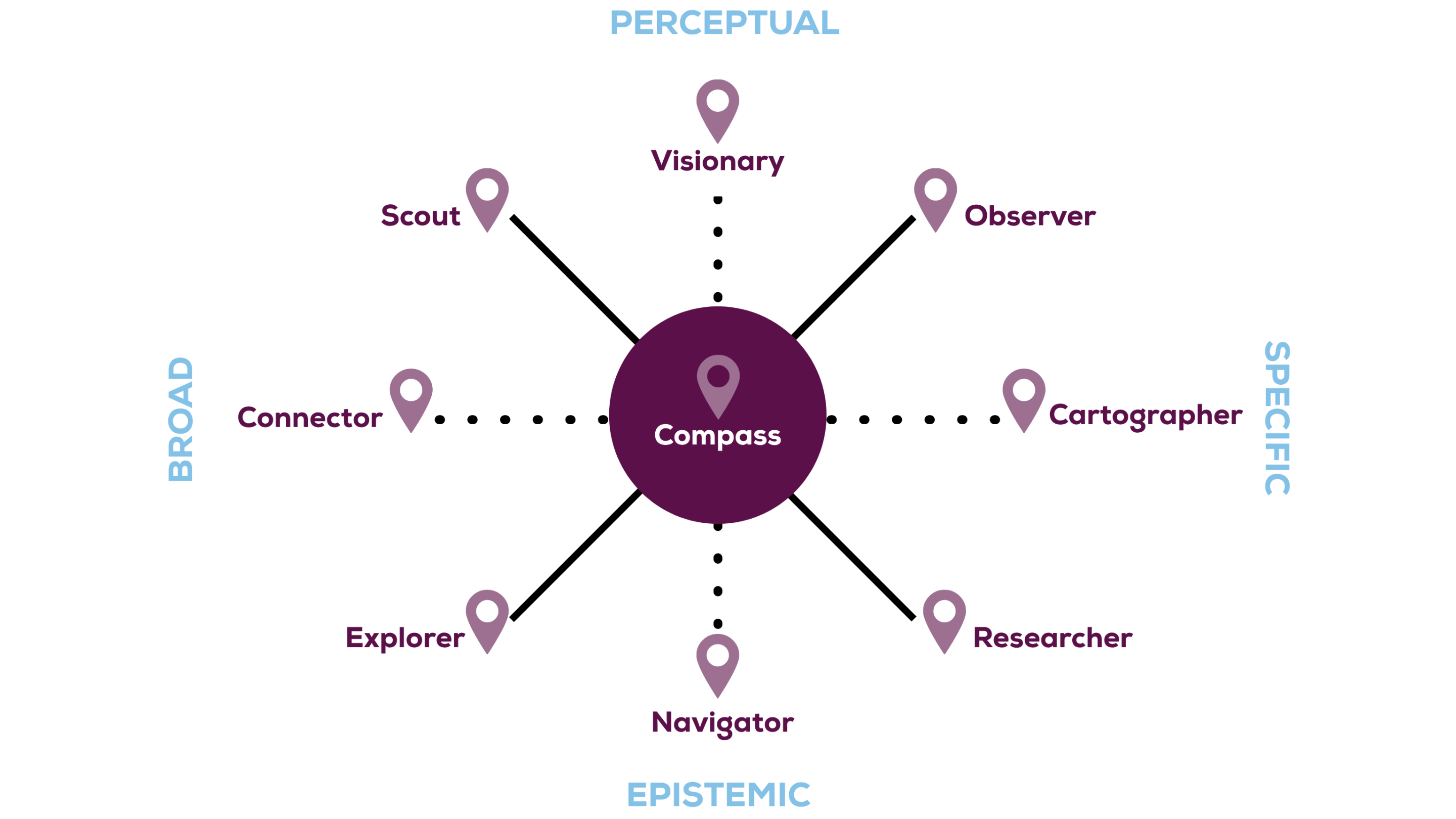

When these axes intersect, they form eight profiles: the “shapes” of curiosity which we’ve used to build profiles and understanding.

There are four core profiles:

Between these sit some complementary types which add nuance: the Visionary, Connector, Cartographer, and Navigator.

At the centre is The Compass. This is a rare profile which moves fluidly between them all, balancing intuition and logic, breadth and depth. The Compass sees the big picture and the fine detail, shifting shape as the question demands.

Darwin would’ve seen himself there.

Recognising the shape of your curiosity isn’t about self-classification; it’s about self-awareness.

If you’re a “Researcher”, you might notice your tendency to stay deep in analysis. If you’re a “Scout”, you might see how easily you drift toward the new at the expense of completion. Knowing this helps you balance, it helps you value what others bring, and it can help you tool-up to move between types as you need to across the responsibilities of your role.

Within organisations, curiosity is often treated as a soft skill but it’s anything but.

The most innovative teams aren’t those filled with one kind of thinker. They’re the ones that make room for many. Imagine a team that starts with Scouts sparking ideas, moves to Explorers to connect them, then draws on Researchers and Observers to test and refine. That’s the pathway from curiosity to innovation.

The challenge is creating environments where all shapes of curiosity are safe to surface, where asking why or what if isn’t seen as a distraction, but as the work itself.

When curiosity is encouraged, people feel trusted to explore, to question, to connect. When it’s stifled - with our research showing time, fear, or hierarchy are the main culprits - understanding shrinks and decisions become shallow.

At Redvespa, we see it as the foundation of good analysis and good business. It’s how we help organisations find clarity: by asking better questions, not faster ones.

When Darwin began his voyage on The Beagle, he didn’t know where his questions would lead. He only knew he had them, and that he was willing to follow them.

He noticed first. The colours of rocks, the beaks of birds, the shapes of shells. Then he wondered, then tested, then returned to wonder again.

Decades later, when he finally published On the Origin of Species, the impact was lightning but the insight wasn’t. It was the patient layering of curiosity in all its forms - perceptual and epistemic, broad and specific - woven together over time.

Darwin was more than a scientist. In our model, he defines a Compass, moving gracefully between curiosity’s shapes to chart an entirely new way of seeing the world.

We don’t know what Darwin’s perspective on curiosity was, or how intentional he was in moving between types of curiosity. We can see in his example, however, that impact comes from utilising curiosity in all its forms - whether that’s within ourselves and our own capabilities, or those of our colleagues and teams.

Link copied to clipboard